I’m a geophysical fluid dynamicist. I’m interested in questions in oceanic, atmospheric, planetary flows, and fluid mechanics. My main research effort is focused on understanding the mean climate state of the atmosphere and ocean. One of my ambitions is to narrow the gap between theory and simulation in climate science.

Ocean

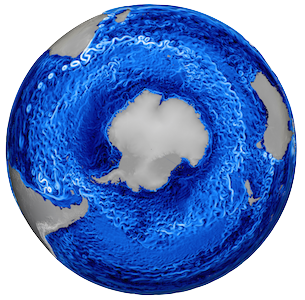

Credit: NASA/JPL

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) is the largest current in the ocean. The geometry of the Southern Ocean enables the ACC to connect all ocean basins. ACC plays an integral role in the global climate, e.g., by setting up the meridional overturning circulation and controlling the meridional heat transfer in the ocean.

The winds over the Southern Ocean that mainly drive the ACC have been strengthening and shifting polewards due to climate-change and ozone depletion.

I am interested on how the ocean responds to climate-change forcing at different time and length scales. For example, how the mesoscale flow features have been changing due to changes in the atmospheric circulation, and also how does the strength of the ACC respond to the increasing strength of westerly winds over the Southern Ocean. In particular, I’ve been trying to delineate the role of barotropic and baroclinic processes that are involved in the ACC’s response to changing winds.

Climate models cannot resolve all length scales of oceanic fluid motions and, therefore, they rely on parametrizing the collective effect the small-scale unresolved motions have on the larger scales that the models resolve. Understanding the underlying dynamics is crucial for developing and improving these parametrizations. I’ve been investigating the role that the intrinsic ocean dynamics (i.e., mesoscale flows and smaller; typically unresolved by coupled climate models) have shaping the large-scale ocean flow at decadal time scales and the effect that these then have on feed back back to the atmosphere via air-sea interactions.

In an attempt to bridge the gap between theory and simulation in climate science, my work has been focusing on probing the dynamics by which the ocean mesoscale eddies and bathymetric features interact with large-scale currents, like the ACC. I emphasize on understanding using theoretical tools aided with a series of conceptual models of increasing complexity, for example, quasi-geostrophic turbulence on a beta plane or a primitive equations-model with modest stratification in a channel.

Atmosphere

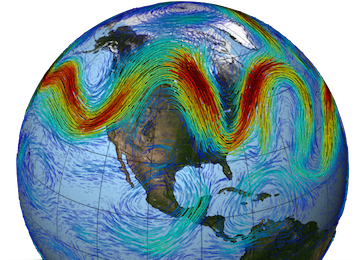

Planetary atmospheres self-organize into large-scale coherent structures that vary on time-scales much longer than those of the turbulence they co-exist with. Prominent examples are the Earth’s subtropical and polar jet streams. Often these coherent features are energized from the surrounding turbulence, i.e., they are eddy-driven. Understanding the dynamics of these large-scale features is vital for understanding the climate.

Credit: NASA GSFC

However, the dynamics of the coexistence of coherent large-scale features and turbulence is difficult to study because many standard techniques, such as classical stability analysis, are ineffective. These methods assume that a mean state exist in the absence of the fluctuations and also disregard the effect of these fluctuations on the mean state. This is not the case in planetary atmospheres where the mean state is inseparably connected with turbulence. Recent developments, some in my doctoral thesis, have broken through this impasse. The key is to study the Statistical State Dynamics (SSD) of the flow; i.e., the dynamics of the statistics themselves rather than of individual flow realizations. One aspect of SSD is a new type of stability theory that addresses mean flows in the presence of turbulent fluctuations.

I have been using SSD techniques to make analytic and numerical predictions regarding the symmetry breaking of homogeneous atmospheric turbulence and its self-organization to jets or large-scale coherent waves, the physical mechanism underlying this self-organization, the mechanism by which the large-scale structures equilibrate at finite amplitude, and also the co-existence of jets, large-scale waves, and turbulence.

Climate is the statistics of the weather; as such, one often identifies climate with long time-averages from a single-realization model run or an observational record. This viewpoint does not allow for dynamical evolution of the climate state. The study of its SSD naturally allows the climate to evolve. Within the SSD, climate and all the eddy statistics are evolved together. Thus the study of its SSD seems a proper way forward. SSD reveals some key relevant physical processes that are often obscure in the single-realization flow dynamics. Many such phenomena are intrinsically associated with the dynamics of the statistical state and have an analytic expression only in SSD. Within the framework of SSD, for the first time we can determine the possible climate regimes as equilibria of the dynamics and, furthermore, study their sensitivity to parameter variations, transitions between these climate regimes, tipping points, etc.

Data-driven, physics-informed ocean model parametrizations

![Machine learning can enhance the accuracy of climate model parametrizations. [GFDL CM2.6 Climate Model]](../img/ML.png)

Credit: GFDL

Despite the effect that mesoscale eddies have in climate, the lateral resolution needed for climate models to resolve mesoscale motions is restrictive for climate projection. Climate projections require climate model runs of hundreds of years. Therefore, climate projections rely on parametrizations. The development of novel parametrizations or the improvement of those currently implemented in climate models relies on a better understanding of the underlying dynamics. Currently, I’m developing a novel parametrization for the ocean’s mesoscale eddy fluxes using data-driven methods and machine learning algorithms.

On 2021, I was awarded a Discovery Early Career Research Award from the Australian Research Council to work on a novel parametrization for the ocean mesoscale using machine learning and data-driven methods. I am using output from eddy-resolving ocean model and physics-informed machine learning techniques to develop better eddy parametrization. Towards this goal, I am actively involved with the ocean modeling team of the Climate Modeling Alliance (CliMA), in developing new software tools that enable seamless interaction between ocean modeling software and machine learning tools. We are currently using these tools to develop and calibrate parametrizations for the mesoscale fluxes and the ocean’s surface boundary layer.

Read more about how machine learning can enhance the accuracy of climate and ocean models in The Conversation.

Gas giants

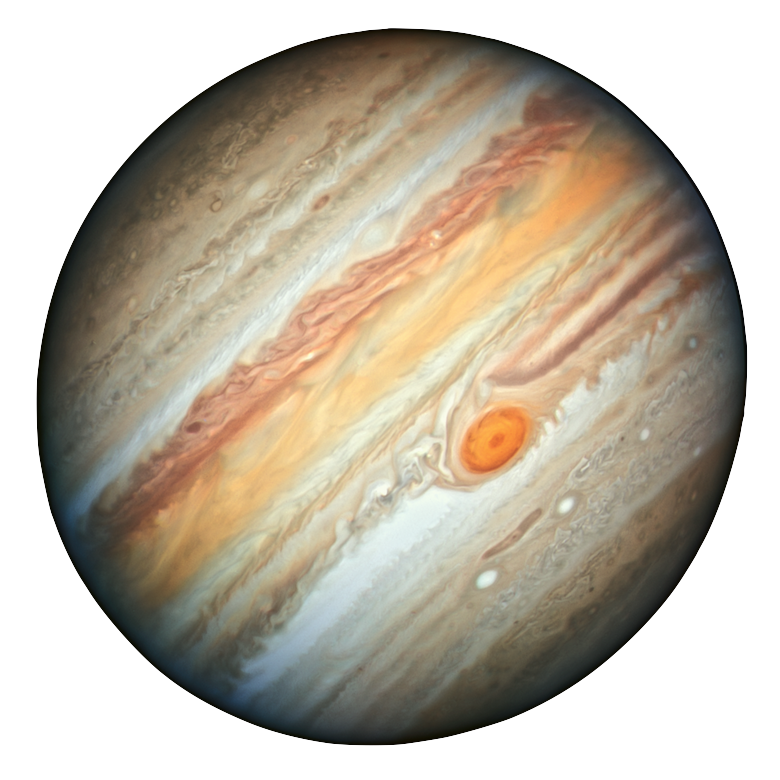

Credit: NASA, ESA, A. Simon and M.H. Wong

With my collaborator Jeffrey Parker, we studied how magnetic fields in the interior of gas giants may interrupt the self-organization of planetary atmospheres into coherent zonal jets. Our results suggest that turbulent magnetic fluctuations when found in an environment with mean shear flows could, effectively, act as an additional viscosity on the mean flow itself. We called this phenomenon “magnetic viscosity.” Simple estimates reveal that this physical mechanism may provide a plausible explanation for the depth-extent of the jets on Jupiter and Saturn as was recently revealed by spacecrafts Juno and Cassini respectively.

Wall-bounded turbulent flows

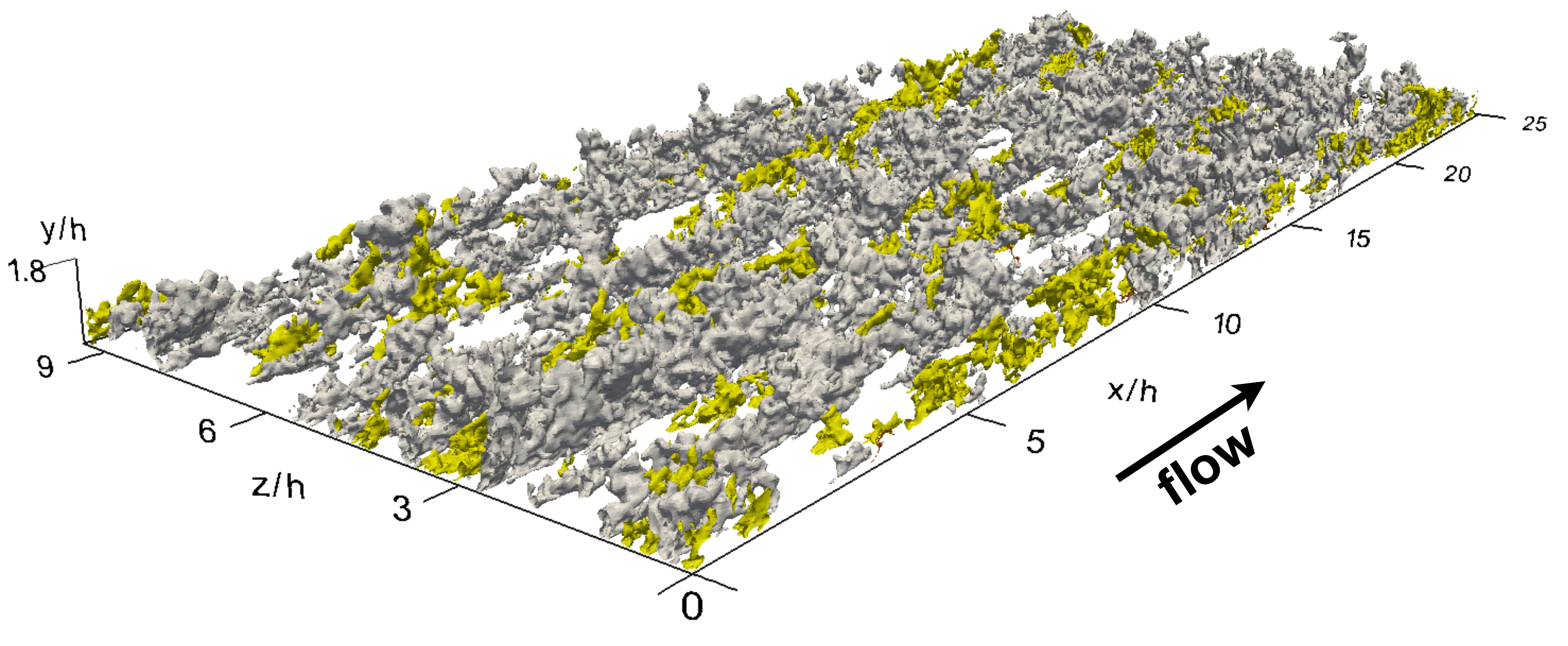

Credit: A. Lozano-Durán

With my collaborator Adrian Lozano-Durán (and others), we have been studying the dynamics of very-large-scale roll–streak motions in three-dimensional flows in regions away from boundaries. The mechanism by which energy feeds from the large-scale motions back to the turbulent fluctuations, thus closing the loop in the self-sustained regeneration cycle of turbulence, remains outstanding. In an attempt to resolve the enigma, we recently demonstrated that the modal instabilities of the streaky coherent structures are not the main players involved in this energy transfer.